Students abusing drugs like Adderall and Ritalin isn’t a new problem: they’ve long been weapons of choice for college kids looking to pull all-nighters. But according to the New York Times, that trend is now trickling down to the high school level. In a lengthy story on the front page Sunday, the Times reported that behind many high achieving students lies a secret addiction to prescription stimulants.

(MORE: ADHD Drugs and Grades: How Big a Problem Is It?)

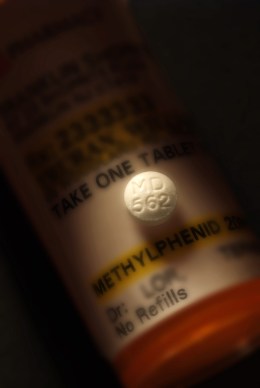

While drugs like Adderall, Vyvanse, Concerta, Focalin and Ritalin — the “good grade pills,” as the story dubbed them — calm people with A.D.H.D., those without the disorder receive an energy jolt from the pills. Students use that jolt to help keep them awake to study or to stay focused during tests like the S.A.T. In fact, since 2007, the number of prescriptions for A.D.H.D. medications dispensed to people ages 10 to 19 has risen by 26%, to almost 21 million yearly, or about two million individuals, the Times reports.

The story details the ease with which students are able to get prescriptions for the pills (“many youngsters with prescriptions said their doctors merely listened to their stories and took out their prescription pads,” it says). One unnamed teen told the Times, “I lie to my psychiatrist — I expressed feelings I didn’t really have, knowing the consequences of it. I tell the doctor, ‘I find myself very distracted, and I feel this really deep pain inside, like I’m anxious all the time.'”

(MORE: Ritalin for Toddlers?)

Beyond the kids-on-stimulants trend, the Times speculates about what effect the drugs may have on these students further down the road. Not only could these pills, which the students often snort lines of, serve as a gateway to narcotics like heroin and cocaine, but abuse of the stimulants can lead to depression, mood swings, heart irregularities, acute exhaustion or psychosis.

“Children have prefrontal cortexes that are not fully developed, and we’re changing the chemistry of the brain. That’s what these drugs do. It’s one thing if you have a real deficiency — the medicine is really important to those people — but not if your deficiency is not getting into Brown,” Paul L. Hokemeyer, a family therapist at Caron Treatment Centers in New York City told the Times.

In the worst case scenario, the story cites one student who became so addicted to the stimulants that he spent seven months at a drug rehabilitation center.

Read the full New York Times story here.

MORE: Getting Distracted from the Real Issues of ADHD

Kayla Webley is a Staff Writer at TIME. Find her on Twitter at @kaylawebley, on Facebook or on Google+. You can also continue the discussion on TIME’s Facebook page and on Twitter at @TIME.