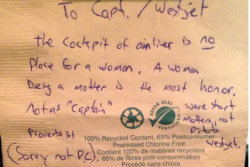

Melville (bottom left) and three search teams in 2009

In the face of disaster, some of the most critical rescuers have four legs.

In 1995, retired schoolteacher Wilma Melville and Murphy, her FEMA-certified search dog, were deployed to the site of the Oklahoma City bombing to aid in the critical search and rescue mission. Alongside six other canine teams, Melville and Murphy combed through the wreckage to seek out survivors and recover bodies of those who had perished. It was an eye-opening moment for Melville, who wondered how the United States could have just 15 search dog teams to aid in disaster response, when in a crisis the size of Oklahoma City, using all 15 could be the difference between life and death.

Gypsy and her handler Tom search through rubble in 2006

With this in mind, Melville returned home to California and planted the seeds that would become the National Search Dog Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to providing the most highly trained canine disaster search teams in the nation. Sixteen years and 77 deployments later, including a recent journey to tornado zone in Joplin, MO, the SDF has played a critical role in aiding rescue missions around the world. NewsFeed spoke with Melville to find out how she turns these dogs from rescued to rescuers.

(LIST: The top 10 heroic animals)

What do you look for when bringing a dog into your program?

Most of [these dogs] are rescued, but some are donated. The dogs we look for are typically not easy to place in a normal home. They’re high energy and high drive. They’re looking for something to do. The dog has to have a tremendous amount of self-confidence. We find that if we have those characteristics, the training turns them from a dog that’s a pain to live with to one who is focused, energetic and does the job well. These dogs will constantly pester you. That kind of energy and drive is difficult to live with, but a pleasure to train. Once they know their job, they are just as happy.

What type of training do these dogs get?

It takes six to eight months of professional training. We begin in the search phase, where they learn the bark alert for live human scent. They are to focus their bark and point their noses to show where the live human scent is coming from. [Sometimes,] we have a dog that won’t bark because they were taught not to. If we can’t encourage them to bark, then we can’t use that dog.

Next, the dogs are taught to search. It takes many small steps to achieve dogs who likes to search. Then the dogs learn obedience and [navigate] an obstacle course. Now, this is not a standard course. The dogs climb ladders and go over slippery surfaces. Because if you put normal dogs on a debris pile, the debris will shift and the dogs will shut down. We have to overcome that tendency. But if it’s the right type of dog, [the course] can be kind of fun for them.

(PHOTOS: Canines in Combat)

The dogs and their trainers are an important team. How do you pair them together?

We don’t start training the dogs until we have the firefighters ready. There’s a great deal of effort that goes into selecting the handlers. It takes about the same amount of effort that goes into training the dogs. [After the handlers are selected], we train them for one week with dogs who are already [certified], so when they’re paired with their own dogs, they have a notion of what’s expected. Then, they’re paired with their dogs and work with them for another week [at our facility]. The dogs love it! Instead of being one of a group, now he’s got his own guy’s attention all day long. They really start to thrive. In about a year, the team is ready for their FEMA certification test.

(VIDEO: Inside the canine mind)

Three things make a successful search team: the right dog, right handler and best training possible. There’s no point in having a highly trained dog with a poor handler. After the dog completes training, it’s worth a great deal. So if we need to place the dog with another handler, we will do that.

Randy Gross and Dusty at Ground Zero on 9/11

You have two teams deployed in Joplin, MO, right now. What are they facing?

When they arrive, there’s a briefing where the people who are running the incident assign the search group to an area delineated on a map. After they finish that area, they can be moved on to another. When searching, they often work a 12-hour shift, but if the handler has the dog moving through debris for 12 hours, they’re making a big mistake. The dogs should work for half hour or 45 minutes, take an hour off, then go back. They can cover a large area, but it’s very hard work. The dog should be put in a crate, have water, relax, then get back up and do it again.

(MORE: Inside the minds of animals)

Why is it important to have these search and rescue teams?

The dog and his nose are the best indicator of where a live person could be found. If you’re looking at acres or blocks of destroyed buildings, a lot of people are there. It’s a question of where are they? Dogs are the fastest to locate the human scent. They are also trained to tunnel, so they can get to the interior of debris, and can indicate to rescuers the direction to remove debris to reach a trapped person.

We currently have 28 task forces throughout the nation, and this year we hope to create 21 new teams. We’re also building a National Training Center to not only train the SDF teams, but all the nation’s canine teams. The deeper we get into [the mission], the more we realize that needs to get done. We’re getting there.

(PHOTOS: Strays to the rescue)