George McGovern, former Democratic South Dakota Senator and two-time Presidential nominee, died Sunday at the age of 90 after a brief illness. An intelligent, confident politician who twice stepped up as his party’s candidate and worked to turn the counterculture of the ’60s into a mainstream political phenomenon, he ultimately remains best known for his vehement opposition to the Vietnam War.

McGovern, a World War II Air Force veteran with Ph.D in History, served for 18 years as the Democratic Senator of a heavily conservative state, during which time he served on the Agriculture Committee and attempted to bridge the deepening rifts within his party. Here’s a look back, through the archives, of TIME’s coverage of McGovern and his career.

(PHOTOS: George McGovern, the Quiet Warrior: Photos From His ’72 Campaign)

Despite the support of President John F. Kennedy, McGovern lost his first bid for South Dakota’s Senate seat in 1960. Having given up his seat in the House of Representatives to run, he instead accepted a position as head of Kennedy’s Food-for-Peace Program in 1961. McGovern traveled the world, negotiating with foreign leaders, but contracted hepatitis during a trip to South America and subsequently lost all his hair. TIME wrote about his colleagues’ reaction to a hairpiece he tried out:

That gleaming dome of the Capitol is all very well, but South Dakota’s Democratic Senator George S. McGovern, 42, found himself emulating it a couple of years ago, as a result of a siege of hepatitis. Last week, while introducing a bill to boost Government-maintained prices on domestic wheat to 100% of parity, McGovern displayed a return to parity himself, with the aid of what the trade calls a “partial hairpiece.” Several of his colleagues thought it was pretty funny, but McGovern silenced them with a farm metaphor. Said he: “When the shingles start corning off the barn roof, you put some new ones on.” (Jan. 29, 1965)

All jokes aside, McGovern emerged as a key opponent of the Vietnam War as early as 1965. Seen as a voice for many critics of the war, he forcefully denounced Nixon’s decision to increase spending on military programs, particularly anti-ballistic missiles, in 1969. TIME captured his ire:

South Dakota’s George McGovern, one of the Senate’s most steadfast antiwar spokesmen, called the ABM decision, “a blunder comparable to the decision to escalate the war in Viet Nam in 1965.” In a speech planned for delivery this week, McGovern aimed one of the bitterest attacks on the war heard since the 1968 election: “We hear that the war is going well; the enemy is tiring; if only we persist in the present course, there will be victory.” Continued McGovern: “The new Commander in Chief must grasp what his predecessor learned to his sorrow—that in any continuance of the war in Viet Nam lies the seed of national tragedy and the certainty of personal political disaster.” (Mar. 21, 1969)

During this period, McGovern was courted by the Dump Johnson movement — a Democratic faction disenchanted with John F. Kennedy’s successor — to run for president, an offer he declined. Robert F. Kennedy accepted the challenge, however, and mounted a campaign that McGovern remained publicly neutral to but privately supportive of. Kennedy’s June 1968 assassination left McGovern distraught, though he stood in for him for a short time leading up to the convention. TIME chronicled their close relationship:

Robert Kennedy was once asked to name the most decent man in the Senate. “George McGovern,” he replied. “He’s the only decent man in the Senate.” South Dakota’s junior Senator felt much the same way about Kennedy. The two were close friends for years, from the time that McGovern took over John F. Kennedy’s Food for Peace program in 1961. (Aug. 16, 1968)

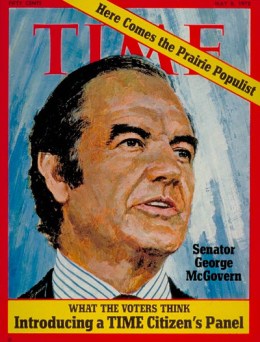

After the convetion, the “gentle” politician was re-elected Senator, leading many to call him a natural candidate for the next election. Well-liked and on good terms with his divided party, he continued his work with agriculture and food committees. He continued his opposition to the conflict in Vietnam, participating in the massive peace march known as the Vietnam Moratorium of 1969 and devising the McGovern-Hatfield act to limit spending on the war. By 1972, as TIME reported in McGovern’s first cover story, he was running for president — a prospect that didn’t please everyone in his party:

The entire McGovern phenomenon—his progress from near-obscurity to something like a fait accompli—has left the Democratic Party in a state bordering on stupefaction. Only now, perhaps too late, are the party’s regulars beginning to shake off their astonishment and think of ways to avert what many of them regard as the disaster of a McGovern candidacy. But thus far no one has produced a candidate, an organization or a plausible scenario to stop McGovern. (Jul. 3, 1972)

Despite his cool, chic persona, party reforms, support for young, educated activists (including Bill and Hillary Clinton), and overall fresh take on a post-’60s America, the “prairie Populist” made a miserable candidate. His first choice for vice president, Missouri Senator Thomas Eagleton, revealed after accepting the post that he’d struggled with clinical depression. McGovern quickly swapped Eagleton for Sargent Shriver, but the impression of waffling and poor judgment the episode left proved deadly to his campaign. McGovern lost all but one state in the Presidential election, a landslide that was practically unprecedented. As Rick Perlstein wrote in TIME last year, the loss wasn’t helped by his failure to remind voters what Democrats had done for them:

Then, in 1972, the Democrats ran a candidate whose speeches were more frantic than any in history. George McGovern, following a then fashionable theory that the middle class was prosperous enough to take care of itself and that unions were pretty much irrelevant, spoke to working-class concerns less than any Democrat had before. He lost 49 states.

McGovern didn’t give what Lyndon B. Johnson used to call “Democratic” speeches — LBJ’s shorthand for talking about which party gave the people Social Security, Medicare and the Tennessee Valley Authority and which one was willing to toss them over the side. LBJ gave such speeches all the time in 1964 — and he won 60% of the popular vote.

Here’s what LBJ knew that McGovern didn’t: There are few or no historical instances in which saying clearly what you are for and what you are against makes Americans less divided. But there is plenty of evidence that attacking the wealthy has not made them more divided. After all, the man who said of his own day’s plutocrats, “I welcome their hatred,” also assembled the most enduring political coalition in U.S. history. (Aug. 18, 2011)

McGovern finally lost his Senate seat in 1980, and briefly ran in the 1984 Presidential election before dropping out and endorsing Walter Mondale. Commonly called the conscience of the Democratic Party, he briefly considered running again in the ’92 race before turning his attention to philanthropy, his work with world food agencies, and writing books on topics like hunger and the Iraq War. President Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2000 for his continued efforts to eradicate world hunger.