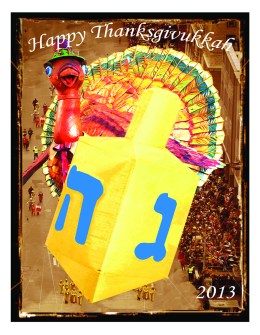

In a rare alignment of calendars, Thanksgiving and the first day of Hanukkah both fall on Nov. 28 this year. And Americans planning to celebrate this double holiday have dubbed it Thanksgivukkah. At first glance, the festivals might seem completely different. One is dreidels. One is pumpkins. One is kosher. One is pigskins. But here are five things the holidays have in common:

Both are a great excuse to stuff yourself silly.

Yes, people eat hot dogs on the Fourth of July and sip eggnog on Christmas Eve, but there is no holiday on the American calendar that is more about food than Thanksgiving. Hanukkah, a time to eat latkes and brisket, kugel and challah, is also celebrated by putting delicious things in bellies. “All Jewish holidays are about food,” says Dana Gitell, the Bostonian credited with coining Thanksgivukkah. “And that’s one of the reasons why American Jews love Thanksgiving so much. These are both feasts.” The convergence has set foodies atwitter, inspiring fusion menus and dishes like turkey doughnuts.

Both are rooted in religion.

Hanukkah, of course, is a Jewish holiday. Known as the Festival of Lights, the eight-day celebration commemorates a Jewish military victory and the miracle of oil that lasted eight days when it should have lasted one. As any fourth grader will tell you, Thanksgiving commemorates a harvest feast among Indians and Pilgrims that happened almost 400 years ago. While that might seem secular, those Pilgrims never would have been breaking bread with those Indians if they hadn’t first broken from the Church of England—and fled Europe in search of religious freedom.

Both were started by groups who found refuge in America.

Rabbi Mishael Zion, co-director of the Bronfman Fellowships, points out that Hanukkah and Thanksgiving were both started by people who found a haven in America and flourished there. “Thanksgiving really celebrates not so much America the country, but America the idea,” says Zion. “It’s a place of refuge. It’s also a place of opportunity and mobility and success.” Freedom from want, he says, quoting Franklin Roosevelt, “is what the Jews have found in America. It’s what Pilgrims found in America.”

Both are all about being thankful.

“They both are holidays of gratitude after facing adversity,” says Zion. Two millennia ago, the Jewish people were thankful that their conflict with Greco-Syrian foes was at an end, he says, and today Hanukkah is a fine time to be grateful for religious freedom. Thanksgiving started as an appreciation of a bountiful harvest and has morphed into a day when people count any and all blessings, being it a lovely family or a day off from school.

Both are a reason to go home.

People aren’t flooding public parks or places of religious worship on either of these holidays. People aren’t reciting long Hebrew prayers or poring over the Mayflower manifests either. These are both celebrations that involve sitting at home, catching up with Gram-Gram. “Thanksgiving and Hanukkah don’t belabor the point,” Zion says. “They are both home holidays.” Gitell says that Thanksgivukkah should be a day for fun and a day for unity. She, for one, will be with her family like she is for every Thanksgiving and Hanukkah. “We’re just going to have more food,” she says.

(MORE: Everything You Need to Know About Thanksgivukkah)