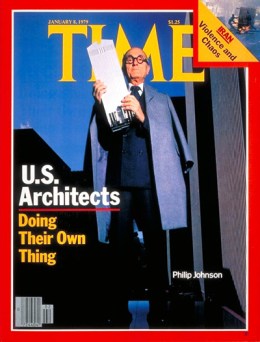

Hughes on the then-unfinished AT&T (now Sony) building in New York:

A T & T is certainly a shift from Modernism, but to where? Apparently, to “Manhattanism”—that fantasy-laden, Promethean language of shaped towers that produced the great monuments of the ’20s and ’30s: Rockefeller Center, Empire State, the Chrysler Building. As the architect Rem Koolhass has argued in his brilliantly suggestive book, Delirious New York (Oxford, 1978), these were the definitive fantasy-structures of American capital, the cathedrals of a “culture of congestion” that finds its apogee in the 1,244 blocks of Manhattan Island. No glass slab could hope to be as rich in imagery as the work of an architect like Raymond Hood (chief architect of Rockefeller Center, designer of the old McGraw-Hill Building and the Chicago Tribune Tower). This point was not lost on Johnson. Fantasy veiled as history: such is the message of A T & T. In the process, Hood is appropriated to the recipe.

A T & T is peculiar rather than radical. Its main element is a 660-ft. glass slab laced into a Beaux-Arts, Manhattanist corset of pinky-gray granite. This shaft sits on an entrance block that is an enormous pastiche of the courtyard front of Brunelleschi’s 15th century Pazzi Chapel in Florence. One cannot guess from drawings or models how well this will work. To take a small, private Renaissance chapel and inflate it to nearly the size of the Baths of Caracalla is the kind of perversity Johnson enjoys but has never been allowed to do on such a scale before. It is architecture mimicking the strategies of Claes Oldenburg. What A T & T will eventually make of this high-camp, post-Pop irony performing as status monumentalism is anyone’s guess, but that is what Johnson has produced, and the fact is emphasized by the top of the building—the now famous “grandfather clock” pediment with its round operculum, through which the heating system will issue clouds of steam on cold days. This is yet another historicist joke, alluding to one of Johnson’s favorites from the past—Boullée, whose vast panoramas of pyramids, masonry globes and smoking crematoria are among the singular documents of the early Industrial Revolution. That a building should have a top was, of course, anathema to Johnson’s mentor, Mies van der Rohe; the glass prism required a flat roof, finished in one clean cut. But since all the great pre-Modernist Manhattan buildings have tops—finials, breadbaskets, cornices, towers—the first big Post-Modernist one must have one too.

MORE: View a complete index of Robert Hughes’ writings for TIME