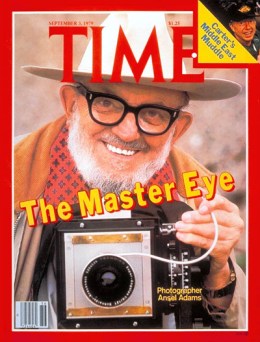

Hughes on famed photographer Ansel Adams:

This sense of a miraculous, beneficent clarity, of vision ecstatically distributed between the near and the far, has permeated American nature writing from Henry David Thoreau to Carlos Castaneda. It is as central to Adams’ photography as it is to O’Keeffe’s painting, or further back to the landscapes of Yosemite and Yellowstone painted by Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Moran and their followers in the 19th century. An entire tradition of seeing is inherent in the word wilderness; it is essentially romantic. As Szarkowski has observed, “Adams’ pictures are perhaps anachronisms. They are perhaps the last confident and deeply felt pictures of their tradition . . . It does not seem likely that a photographer of the future will be able to bring to the heroic wild landscape the passion, trust and belief that Adams has brought to it.”

The wilderness, for most Americans, is more a fable than a perceived reality. Ecologists and preservationists have made it a moral fable, an emblematic subject drenched in quasi-religious conviction. But this does not make it any less fabulous. The family in the Winnebago, lurching toward Yosemite to be reborn, cannot experience what in the 19th century used to be called the “Great Church of Nature” as it is seen in Adams’ photographs: the experience has become culturally impossible. That has also worked to Adams’ advantage. By now, his photographs of lakes, boulders, aspens and beetling crags have come to look like icons, the cult images of America’s vestigial pantheism.

MORE: View a complete index of Robert Hughes’ writings for TIME