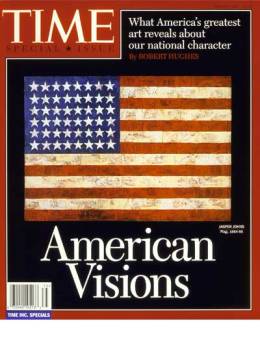

The fact of immigration lies behind America’s worship of origins, its intense if erratic piety about the past–which combines sometimes with a perplexing indifference to its lessons. In America the past becomes totemic, and is always in a difficult relationship to the great central myth of American culture, the idea of progress and newness.

For the New World really was new, at least to its European conquerors and settlers. It fostered a passionate belief in reinvention and in the power to make things up as you go along, which is an important form of freedom. This and a hankering for origins are both strong, contradictory urges. They produce closely twined feelings: on the one hand a sense of freedom to act in the present and future, and on the other a nostalgia for the past. These lie at the heart of all immigrant experience and are summed up in America as nowhere else. The art Americans have made often testifies to this.

A culture raised in immigration, through the piling of arrival upon arrival in an adopted land, cannot escape feelings of alienness. A faith in redemptive newness is what makes up for the whisper of unease at the loss of origins. Both are present in the growth of American art and architecture, which begin weakly and derivatively in the 17th century but acquire seemingly irrefutable power by the late 20th.

MORE: View a complete index of Robert Hughes’ writings for TIME