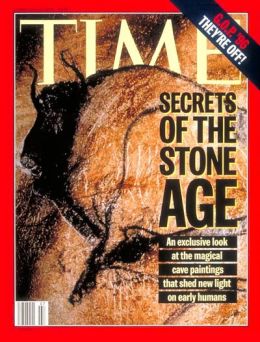

Hughes on Paleolithic cave paintings:

Most striking was their yearning to make art in permanent places — the walls of caves. This expansion from the body to the inert surface was in itself a startling act of lateral thinking, an outward projection of huge cultural consequence, and Homo sapiens did not produce it quickly. As much time elapsed between the first recognizable art and the cave paintings of Lascaux and Altamira, about 15 to 20 millenniums, as separates Lascaux (or Chauvet) from the first TV broadcasts. But now it was possible to see an objective image in shared space, one that was not the property of particular bodies and had a life of its own; and from this point the whole history of human visual communication unfolds.

And:

Modern artists make art to be seen by a public, the larger (usually) the better. The history of public art as we know it, across the past 1,000 years and more, is one of increasing access-beginning with the church open to the worshippers and ending with the pack-’em-in ethos of the modern museum, with its support-system of orientation courses, lectures, films, outreach programs and souvenir shops. Cro-Magnon cave art was probably meant to be seen by very few people, under conditions of extreme difficulty and dread. The caves may have been places of initiation and trial, in which consciousness was tested to an extent that we can only dimly imagine, so utterly different is our grasp of the world from that of the Cro-Magnons.

MORE: View a complete index of Robert Hughes’ writings for TIME